There are few songs in American popular culture that are as iconic as “Over the Rainbow” from The Wizard of Oz. It is surprising to think that the song was almost cut from the movie. Written by Harold Arlen and E. Y. Harburg, the lyrics encapsulate the meaning of the film. They express the protagonist’s dissatisfaction, as well as her feelings of powerlessness.

The melody of the song complements the lyrics, and serves as an analog for the journey taken by the protagonist. This is accomplished through contour. We can think of the tonic of the key (scale degree one), as functioning like ‘home.’ Likewise since the first note of the melody is the tonic, this statement is doubly true. The opening melodic interval is a leap up an octave. We can think of this leap as being dissonant, in terms that we are leaving the home of the first note of the song.

This leap is resolved melodically through a structural stepwise descent of the melody. While this may initially be difficult to see, it is very plain if we look at the structure of the melody. We can do this by selecting the most important note of the melody for each measure of music. This begs the question of what makes one note more important than other notes? Emphasis of one note over another happens through duration, volume, and range or tonal concerns. The importance of duration and volume is pretty clear and intuitive. If a note is held longer, or is played more loudly, we will certainly hear it as being more important. Implicit in the question of volume though is the issue of metric placement, meaning that notes that are played on beats one or three (in music that descends from the Western classical tradition) tend to be played more loudly than other notes.

The issue of range and tonal concerns is a bit more difficult to define. That being said, notes that are higher or lower than other notes in a passage tend to stand out. Likewise, notes that have strong tonal implications (dissonance) such as the the leading tone, may stand out more than other, more stable notes.

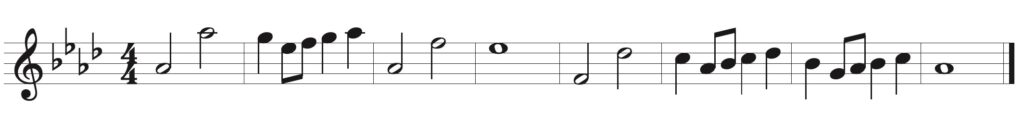

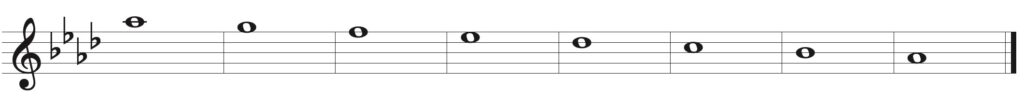

Let’s explore this reduction by looking at the melody of the verse (figure 1). Measure four and eight are self explanatory, as there’s only one note in each of those measures. In measures one, three, and five we could imagine picking the highest note in each measure. In measures two, six and seven if we pick the note that happens on beat one, it is also the most emphasized note, as in each case that note recurs on beat three, taking up half of the measure in all. If we look at all of these notes selected for the reduction what we get is a descending scale (figure 2).

Figure 1: Verse melody “Over the Rainbow”

Figure 2: Verse reduction “Over the Rainbow”

Once you notice this structural descending scale it is hard to ignore. Again the dramatic leap up an octave in the first two notes can be thought of setting up a dissonance that is resolved through the systematic structural stepwise descent of the melody back to the lower octave tonic (the last note). This leap and descent can be thought of as a musical analog of the rainbow mentioned in the song’s title. The melodic motion also reflects the story of the movie. where the protagonist goes on a dramatic journey away from home, only to take on a methodical quest to find a way to return.

The melody in the bridge of the song ascends, but this ascent is not nearly as methodical as the descent of the verse. In that regard, it is probably best to think of this ascent as functioning as a contrast to the verse, rather than to think of it in terms of a metaphor. That being said, the structural use of contour in the verse of “Over the Rainbow” serves as a prime example of how contour can be used for both musical interest as well as a metaphor that can embody the meaning of lyrics or a narrative.