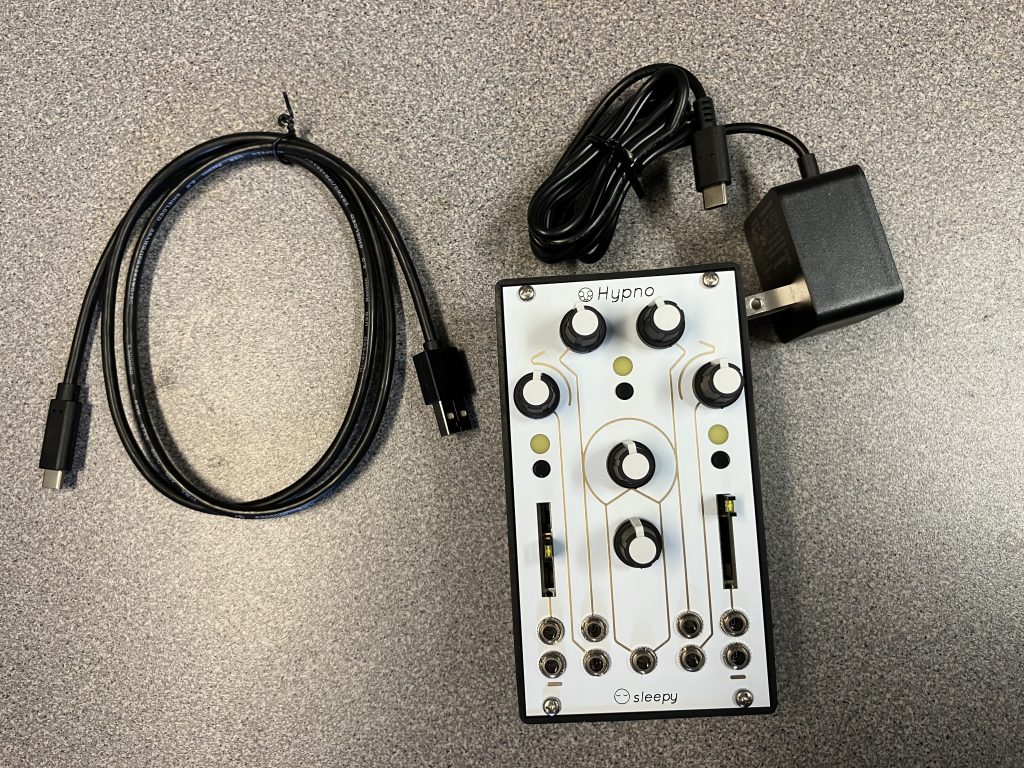

Well, color me excited. Spoiler alert, this experiment was pretty darned successful for a few reasons. I’ll save those reasons for later in the post (that’s what we call a teaser in the business). The experiment at hand was to create a music video for the third track of Point Nemo using control voltages to automate settings on the Hypno. While my previous experiment also entailed using control voltages to automate parameters of the Hypno, that experiment focused on smooth flowing changes provided by sine waves.

For this experiment I focused on instantaneous changes primarily using a step sequencer. In particular, I used Behringer’s clone of Moog’s classic 960 sequencer (lower left in the image below). Since control voltages are literally just voltages that are applied to individual modules in order to alter a setting or parameter, a step sequencer is typically a series of knobs or sliders that are used to set individual voltages. These voltages can then be stepped through in sequence, potentially providing a melody or another repeating musical function.

The Moog 960 has three rows of eight knobs. Each row has two identical outputs. Accordingly, when the 960 is being used, it can output three different sequences of voltages. Furthermore, each row has a multiplier switch with three modes, 1x, 2x, and 4x. Thus, each successive setting generates a wider range of voltages. The speed of the 960 can also be controlled by sending individual gate signals to the shift control on the module’s lower right side. Since a gate signal is just an on or off signal, you can actually use a low frequency oscillator set to a square wave to provide a chain of gate signals. To make things even more complicated, I controlled the frequency of this low frequency square wave with a low frequency sine wave, resulting in the tempo increasing and decreasing in an undulating wave.

As mentioned in the previous experiment, that Hypno has seven CV inputs. The three outputs of the Behringer 960 covers three of these. I covered another two of them by using the same sample and hold setup that I mentioned in the previous experiment, including one being fed pink noise and the other being fed white noise.

The final two control voltages sent to the Hypno came from envelope generators (EG). Envelope generators are intended to provide sculpted sound settings that approximate the nature of acoustic sound. Most envelope generators reduce sound into four stages: attack (the time it takes for a sound to hit full volume), decay (the amount of time it takes for a sound to come down from full volume), sustain (the level at which a sound sustains when it is being held), and release (the time it takes for a sound to become inaudible).

Envelope generators are triggered by a gate signal. Fortunately, the 960 has gate outputs for each of the eight repeating steps of the sequencer. Thus, I attached the fourth gate to one EG and the eighth to another EG. I then fed each EG to its own attenuator to allow me to easily increase or decrease the effect of each. One of these two envelope generators was used to control the zoom control of oscillator B of the Hypno, which is very noticeable, causing the size of the shape generated by oscillator B to grow and decrease in a very rhythmic, predictable manner.

Since this experiment is focused on instantaneous changes, I decided to also use one of the two gate inputs for the Hypno. In particular, I fed yet another gate output from the 960 to the gate input for oscillator B of the Hypno,. This cycles the shape control for the second oscillator of the Hypno.

As stated earlier, I found the results of this experiment to be highly satisfying. First off, the use of the step sequencer provided a visually rhythmic result, which somewhat balances visual variety and consistency. This made improvising with the system a lot more manageable. The system itself provided most of the variety, leaving me to make an occasional tweak to keep things interesting.

For the video input I used a USB drive that had both the video that I used to create the previous experiment, as well as the video of that experiment. Thus, when improvising live with the system I regularly switched back and forth between the original (unprocessed) footage of the sun glinting off of waves of the ocean, and the heavily processed video of that footage that appears in the music video for the last track of the album. Thus, in this video the viewer can still frequently recognize the source of the video, namely sun shinning on waves. I also regularly changed the setting for the type of feedback used by the Hypno. Finally, I often found changing the overall hue and saturation levels of the Hypno to create satisfying results. To summarize what I’ve learned from this, if you use automation to control various parameters in an effective way, this greatly reduces the task of performing other changes live, allowing the improvisor to focus on just a few parameters.

The final satisfying element of this experiment is that I did not have a single connection drop in the HDMI cable, so I was able to record the entire video in a single pass, requiring minimal editing when assembling it into a music video. This really approaches my goal of being able to create a perfectly adequate music video nearly in real time. Now I can shift some of my focus in learning how to use the parameters of the Hypno in a variety of ways, so each music video can be somewhat unique rather than seeming like a cookie cutter of every other video I create using the Hypno.